How Much Can You Trust Your Local Government's COVID-19 Data?

- Audrey Bertin

- Jul 8, 2020

- 10 min read

Updated: Jul 28, 2020

If you are anything like me, you’ve probably been patiently waiting for detailed COVID-19 data to be released, excited about the potential opportunities for future analysis and visualization. As more and more cities make their data publicly available, however, uncertainties and questions will certainly arise.

In my opinion, one of the most important questions that you will have to ask yourself before engaging with any data is:

“Can I trust that these data accurately represent the situation?”

My goal with this post is to hopefully give you a start in answering this.

For the past few months, I have had the privilege of participating in the COVID-19 data collection process at the health department of a major US city.

Although the specifics of data collection and its challenges vary by city and state, and the way in which things worked at my office is not universal, two things have become very clear through my work:

No matter how many resources you have, COVID data collection is never easy.

Something will always go wrong. Often, more than one thing.

To understand why, let’s take a look at how COVID data is processed at my department and some of the ways in which errors can find their way in.

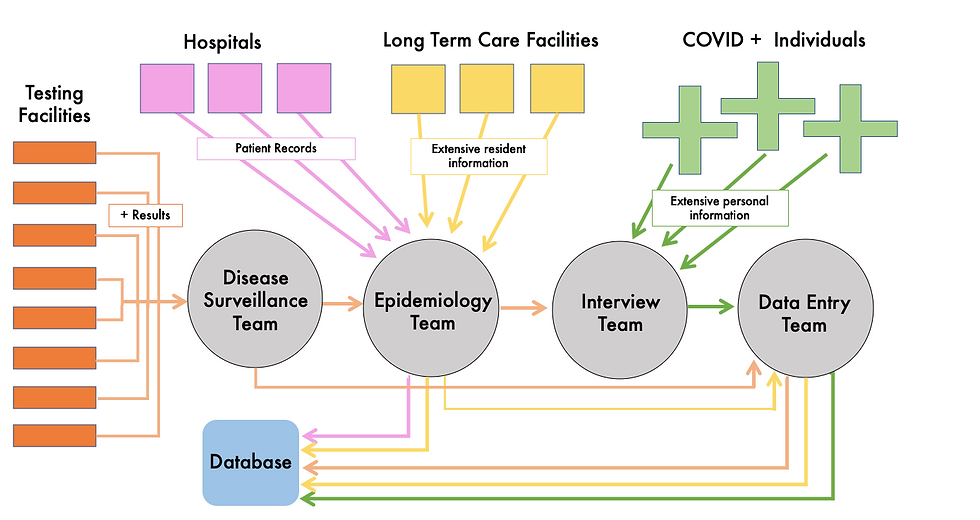

Overview of the Data Collection Process

For the majority of the time that I have been employed, the data collection process has been relatively constant, consisting of three distinct steps:

1. Case Creation:

As soon as someone tests positive with a COVID-19 PCR and the city health department receives a copy of their lab result from the testing facility, they become an official case. The surveillance team collects their lab result and hands it off to someone from the data entry team, who enters the positive individual's basic information (name, DOB, sex, test collection date, etc) as a new entry into the COVID case database.

2. Interviews:

The lab is then handed off to the epidemiology team. The epidemiologists assign the case to an investigator, who is then tasked with the job of collecting additional data on the infected individual. They do this by calling them on the phone and asking a lengthy series of interview questions, which they record the answers to on an electronic form. For long term care facility residents (nursing homes, assisted living facilities, etc), the patients cannot participate in these interviews themselves, so the health department instead works directly with the facility to collect the information on each COVID + resident.

The interview questions asked cover topics such as the infected individual’s race/ethnicity, occupation information, potential exposure history, symptoms, onset/recovery dates, and their pre-existing conditions, among other things.

3. Data Entry:

After each interview is completed, the interviewer uploads their completed interview

form to a shared drive (or in the case of long term care facilities, the facility sends it by secure message to the health department). The form is then printed and joined with their test result sheet and handed back to the data entry team. Whoever is given that case to enter then reads what was recorded on the interview form and manually updates the individual's database record to include the extensive interview data on top of what was already present from the lab. At this point, the case is considered completed, and that record is filed away.

Concurrently with all of these steps, the health department receives patient records from local hospitals indicating when COVID + patients are admitted, when they’re discharged, or when they die. These are often sent to the epidemiologists, who sometimes enter the hospitalization information themselves and other times just attach it to the case and give it to the data entry team.

Here's a visual of how the pieces fit together:

Challenges and Common Errors

There are a big number of moving parts, and every step has countless opportunities for error. In the past several months, I have seen a huge number of mistakes ranging significantly in type. Here are some of the more frequent errors and challenges I've come across, broken down by the step in which they occur:

Step 1: Case Creation

More than 20 different laboratories send in test results, and all do so through different methods. Some use electronic delivery systems–often unique to their lab–while others only provide lab results through old-school paper fax. The significant number of data sources and lack of consistency in how they communicate with the health department make it challenging to keep up with results as they come in. Since labs send both positive and negative results, labs can sometimes get mixed up in the shuffle and negative lab results can be entered as cases into the database when they should not be. Labs sent by fax have the potential to be misplaced before being entered with no easy way to know which ones are lost.

Many of the laboratories doing testing do so on a large scale. Sometimes, they accidentally send test results of people whose residences are outside the jurisdiction of the health department. The disease surveillance team often catches these errors and removes those labs from the stack of new cases each day. However, due to high volumes of cases coming in, some can still slip through.

Step 2: Interviews

Sometimes, people do not provide an address or phone number when getting tested. Other times, the address and/or number provided does not exist or does not actually link back to the correct person (either due to an error in typing or potentially to a specific choice from the individual getting tested to provide inaccurate information). In those cases, it is often impossible to actually contact the case and collect any data. As a result, there is a significant amount of “Unknown” information in the database. Without knowing the details of individuals who we are unable to contact, it is hard to know if the unknown data points can be considered missing completely at random (MCAR), missing at random (MAR), or missing not at random (MNAR). I would hazard a guess, however, that MNAR is the most likely scenario (perhaps with a correlation to race/ethnicity, income, and/or citizenship status) and there is probably some bias in terms of which data points are available and which are not.

Even if the provided contact information is correct, some people never answer the phone. Those that do sometimes refuse to be interviewed, often stating that they’re tired of thinking about COVID or that they’ve already been called by someone who’s working on contact tracing and don’t want to talk to anyone else. Their data gets entered as “Unknown” as well, leading to similar concerns about biases in the missing data.

Even if we succeed at getting an interview, people will sometimes not answer some of the questions. Race and ethnicity questions are not answered on some occasions, often due to interviewees seeing them as very personal and not necessary to know. Occupational information is not provided in some cases because people are scared of being fired from their jobs if it comes out that they are COVID +. Note that this problem is likely somewhat dependent on state law; in at will employment states (which includes the state I have been working for), employers can fire their employees for no reason, and that likely makes people more wary of sharing that information than in states that have laws to better protect their workers.

There’s some information that people can’t always accurately provide because they just don’t know it. This includes symptom onset date (particularly if people are contacted long after their illness started) and comorbidities (some people do not regularly go to the doctor, so may not know what pre-existing conditions they have).

For people that only had one or two symptoms, especially ones that aren’t specific to COVID-19 (headache, runny nose, cough, etc.), they sometimes don’t even realize that what they had are COVID symptoms. They therefore report themselves as asymptomatic when they actually aren’t, and the data reflect this inaccuracy. In a similar vein, people whose symptoms begin very mild, with something like a headache, and then later escalate to more severe symptoms sometimes report their onset as the start of the more severe covid-specific symptoms rather than the start of the mild symptoms, which would be the more accurate date.

The timing of interviews varies widely. Sometimes people are interviewed within a few days of getting tested. Those individuals can still be in the viral incubation period and may report themselves as asymptomatic at the time. Due to high case volumes, people are typically only interviewed once, so if those individuals happened to develop symptoms later, it would not be reflected in the data. When people are interviewed long after they’re tested, different issues arise. For example, when people are interviewed three or more weeks after they are tested, they can more easily forget the details of their illness or to feel “done” with it–especially if they have already recovered–and not want to share much information.

Interviewers all conduct interviews to different degrees of thoroughness. For example, some go through every symptom one by one, asking something along the lines of “Did you have [x]? What about [y]?” and covering all possibilities while others just ask “what were your symptoms?” without giving options. These styles can lead to very different answers, affecting data consistency. Additionally, some interviewers occasionally skip certain sections of the interviews completely.

The interviews have a significant number of questions, but often need to be completed quickly in order to prevent long backlogs. As a result, it is common for interviewers to mark things in error on their interview question sheet, or to provide contradictory information. This makes it very challenging for the data entry team later, who then has to look at the information and make a best guess of what was correct and which parts were entered in error. Some examples of common errors include:

- Marking a patient as asymptomatic but giving a symptom onset date

- Saying a patient has NOT recovered from their illness but giving a recovery date

- Marking both yes and no to the same question

- Marking that the case had no known exposures to COVID while also marking that

they had a close contact interaction with someone who was COVID +

Since COVID-19 is caused by a novel virus, we are constantly learning more about it. This means that the questions asked during interviews change over time. For instance, early versions of the interview forms did not ask about occupation while current ones do, and the list of available symptoms to check off has changed significantly (questions about pneumonia are no longer asked, though they were previously, and loss of taste/smell has been added, among other things). This causes a notable problem with consistency, creating more data points that are missing not at random as the records for old cases are backfilled with “Unknown”s to account for the new questions.

Long term care facility residents, who often cannot be directly interviewed, have a unique set of challenges for data collection. Their interview forms are often filled out on behalf of them by the director of nursing at their facility or, in some cases, an important member of the administration. If those individuals filling out the form do not know the answer to a question, they typically cannot just ask the COVID + resident, as would be possible in normal interviews, and instead must either make their best guess or leave the question blank, leading to a potential for mistakes and missing information. Since the staff members filling out the forms are often in crisis management mode trying to deal with severe outbreaks at their facilities, it is easy to make errors. Patient birthdates can get switched with one another or mistyped, symptoms/comorbidities can be forgotten, etc. Additionally, due to their advanced age and/or pre-existing conditions, long term care facility residents tend to have higher fatality rates from COVID-19 than other populations. This leads to some cases where individuals pass away before they can have their symptoms properly recorded.

Step 3: Data Entry

After interviews are completed, they are printed, combined with lab results, and then entered manually into an electronic database. Due to high case volumes, there are a large number of people who participate in this process and new staff have to be hired constantly to keep up. Due to the fact that some higher-up staff members work remotely, staff schedules are very non-traditional (since the health department has to have workers over the weekend and in the evenings in order to accurately update the data every day), and there are a huge number of employees working on COVID-19, clear communication between all involved is incredibly challenging. As a result, decisions by higher-up staff on how the data should be presented are not always communicated consistently to the data entry staff.

Due to the chaotic and ever-changing nature of the pandemic, a lot of decisions have to be made on the fly and it is difficult to regularly get everyone in charge together to make executive decisions on how things should be handled. As a result, there are no consistent guidelines given to employees on how to enter data, so new staff just mostly learn how to do so by asking questions of those who have more experience. However, the more experienced staff to whom questions are brought are not always on the same page as one another and have differing opinions, so depending on who is asked, you may get a different answer to the same question. Let’s consider the example of hospitalization. When do we mark someone as hospitalized? Is it only when a case is hospitalized because of COVID symptoms or also when someone tests positive while in the hospital, even if admitted for a different reason? Some say it is the first, and some say it is the second, but thesre is no executive decision that is clear and understood by all staff. This means that variables may not necessarily mean the same thing across all cases.

Additionally, data entry staff enter their information in different levels of detail from one another. Some enter just the required information while others are much more thorough, providing a value for every variable, even if that value is “Unknown.” The meaning of “Unknown” vs. just a blank entry then becomes blurred.

Key Takeaways

As I hope has become clear, there are many ways that COVID data collection can go wrong. This is true even within a health department in a big city that has the funding to handle large-scale data collection and had extra time to prepare to address any challenges due to its location in one of the later-hit states. I can only imagine the challenges faced by other departments around the country.

So, in answer to the question I posed at the beginning – “Can I trust that these data accurately represent the situation?” – I say this:

Even COVID-19 data that seem complete and high-quality on the surface likely have issues that are hidden from view. Proceed with caution when attempting to draw conclusions from them and take the time to research and account for the potential faults they may contain. It may require more effort, but it is far better to be thoughtful and careful in your analysis than to produce work that doesn’t accurately represent reality.

Comments